Wednesday, February 22, 2017

7:30 pm WPAC Concert Hall

$15 general, $10 senior, FIU faculty and staff, $5 student, Free for FIU students

2017 MIGF Festival Pass

is available to attend all festival events at a single reduced price: $60 general, $45 senior, FIU faculty & staff, $25 student

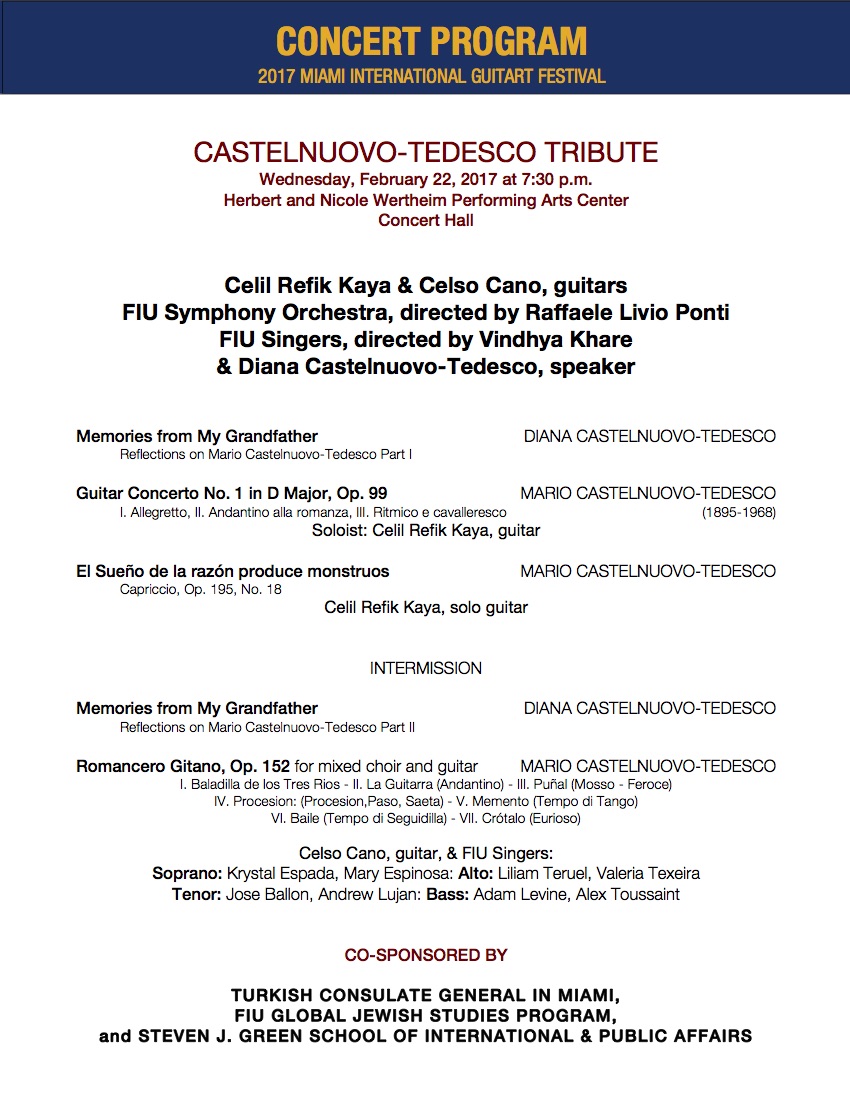

The Miami International GuitART Festival celebrates the musical legacy of Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (1895-1968), one of the foremost guitar composers in the 20th century. Born in Florence, Italian composer Castelnuovo-Tedesco was descended from a prominent banking family that had lived in Florence since the expulsion of Jews from Spain in 1492. Castelnuovo-Tedesco was first introduced to the piano by his mother, and he composed his first pieces when he was just 9 years old. He migrated to the U.S. in 1939 and became a film composer for MGM Studios for some 200 Hollywood movies and wrote almost 100 compositions for guitar, some of which were written and dedicated to the legendary Spanish guitarist Andrés Segovia.

The concert program includes Guitar Concerto No. 1 in D major, Op. 99, Romancero gitano, Op. 152, for mixed choir and guitar, and solo guitar works by Castelnuovo-Tedesco, featuring FIU Symphony Orchestra directed by maestro Raffaele Livio Ponti and guitarists Celil Refik Kaya, winner of the 2012 JoAnn Falletta International Guitar Concerto Competition, and Celso Cano, winner of the 2014 Florida International University Concerto Competition, as well as the FIU Singers, directed by Vindhya Khare. Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s granddaughter Diana Castelnuovo-Tedesco will also making a special presentation “Memories from My Grandfather” during the concert. If not for the insistence of Andrès Segovia, Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco would likely never have composed for the guitar. Today, Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s guitar compositions are among his most celebrated works. Diana reflects on this extraordinary friendship, her grandfather’s admiration of Spanish culture, and other family memories.

El Sueno de la Razón Produce Monstruos by Castelnuovo-Tedesco:

Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s Life and Works

[From Grove Music Online, written by James Westby]

Life

His formal musical education began at the Istituto Musicale Cherubini in Florence in 1909, where he received his licenza liceale in 1913 and his degree in piano the following year. In 1918 he completed the diploma di composizione at the Liceo Musicale of Bologna. The most important musical figure in Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s early development was Pizzetti with whom he began to study in 1915. Pizzetti helped to bring him to the attention of Casella, who became an ardent supporter and whose patronage was crucial at the start of his career. In 1917 Casella, along with Pizzetti, Malipiero, Respighi, Gui, Carlo Perinello and Tommasini, formed the Società Italiana di Musica (later Società Nazionale di Musica Moderna); though not a founding member, Castelnuovo-Tedesco was strongly identified with the group. His reputation was further enhanced by performances sponsored by the Italian branch of the ISCM, which, over an 18-year period, put on more of his music than any other Italian composer other than Malipiero.

In addition to composing, he was a successful performer (as soloist, accompanist and ensemble player), critic and essayist. Described as a writer who ‘demonstrated a quick-witted common sense and a good-natured scepticism for the new … [an] attitude that came from his inborn aversion to any art that is characteristically fanatic’ (F. D’Amico), he contributed criticism extensively to La critica musicale (1920–23), Il pianoforte (1922–5) (later Revista musicale italiana) and La rassegna musicale (1928–36).

By the early 1930s Castelnuovo-Tedesco became increasingly concerned for Italian Jewry, and when Heifetz approached him for a concerto (I profeti, 1931), he saw an opportunity to take a stand, later commenting (in 1940) ‘… I felt proud of belonging to a race so unjustly persecuted; I wanted to express this pride in some large work, glorifying the splendour of the past days and the burning inspiration which inflamed the envoys of God, the prophets’.

In the summer of 1939, shortly before the outbreak of war, he left with his family for New York, staying in Larchmont for a year and a half before moving to California. There, in autumn 1940, he signed a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Meyer, beginning a relationship (from 1940 to 1956) with several Hollywood studios including Columbia, Universal, Warner Brothers, 20th-Century Fox and CBS. During this time he also composed over 70 concert works, including songs and opera, the high-point of his postwar career occurring in 1958 when the opera The Merchant of Venice was awarded first prize in the Concorso Internazionale Campari. Sponsored by La Scala, it was given its first performance in 1961 at the 24th Maggio Musicale Fiorentino.

Castelnuovo-Tedesco had become a US citizen in 1946 and until his death was affiliated with the Los Angeles Conservatory of Music (later California Institute of the Arts). He was one of the most sought-after teachers of film music, his pupils including Goldsmith, Mancini, Previn, Riddle and John Williams.

Works

His early compositions, often considered too ‘progressive’ by audiences, were influenced by Pizzetti’s austere contrapuntalism, Debussy’s Impressionism and the neo-classicism of Ravel. He also experimented with unconventional harmonies, and developed a distinctively refined vocabulary based on successions of parallel chords, polytonal blocks of sound and a fluent counterpoint. Specific imagery is often the basis of his work: Il raggio verde, for example, represents the sun setting over the sea, sending out a final green ray, while the Tre fioretti di Santo Francesco was conceived as a set of frescoes to interpret Giotto’s paintings of the same name. A contemporaneous account described his music as ‘[reflecting the Florentine countryside] with soft undulating lines, all delicately traced by the whole gamut of colours, grays and greens of every hue’ (Gatti, 1918).

However, his brand of neo-classicism also reveals a reliance on traditional forms and an interest in early Italian music history. The Concerto italiano in G minor (1924) for violin and orchestra is a potpourri in the style of Vivaldi with themes modelled on 16th- and 17th-century Italian folk songs, while his finest neo-classical work, the Guitar Concerto no.1 in D (1939), adopts a Mozartian concerto style, the instrumentation intended, as he put it, ‘to give more the appearance and the colour of the orchestra than the weight’. Its success was immediate, Segovia considering it the main work that convinced others of the viability of balancing guitar with orchestra. There is little doubt that Castelnuovo-Tedesco’s most recognized contribution has been his body of almost 100 works for the instrument [guitar].

Though the various phases of his music suggest certain general categories, Castelnuovo-Tedescohimself, as he put it in 1950, ‘never believed in modernism or in neo-classicism, or in any other isms’. Music for him was above all a means of expression, going as far as to claim that everything could be translated into musical terms: ‘the landscapes I saw, the books I read, the pictures and statues I admired’. Three themes were central – his place of birth (Florence and Tuscany), the Bible and Shakespeare. His first theatrical attempts were all on Florentine subjects – the opera La mandragola, incidental music to Savonarola and the ballet Bacco in Toscana, while Shakespeare led him to write some of his most innovative and dramatic music including two operas, 11 overtures and numerous songs.

As his style evolved it became both increasingly neo-Romantic and programmatic. The late String Quartet no.3 (1964), for example, exhibits a narrative structure, recalling a trip to his friend Bernard Berenson’s villa near Settignano: the first movement portrays the hills above Florence, the second describes an intact medieval abbey, the scherzo depicts a train that ran from Florence to Vallombrosa before World War I, while the final movement recreates a conversation between Castelnuovo-Tedesco and Berenson. Of his music for film, Castelnuovo-Tedesco was involved, to various degrees, with some 250 projects. They fall into four categories: scores for which he was co-composer or subordinate composer (these forming the largest number, particularly for MGM); films for which he composed the complete score, including René Clair’s And Then There Were None; films for which he provided specific source music such as the ballet in Down to Earth (1947) and the opera scenes in Everybody Does It (1949) and Strictly Dishonorable (1951); and instances where previously composed film music was tracked into new films. Despite his efforts, he was seldom given screen credit, and described himself as a ‘ghost writer’.

[From Grove Music Online, written by James Westby]